Viewpoint on Value

January/February 2013

Do I really need an appraisal expert?

DIY valuations can lead to inequitable divorce settlements

Valuators can play a supporting role in business growth strategies

Replacement compensation Q&A Why these valuations pose challenges for experts

Visual aids have a strong impact

765 Post Road. Fairfield. Connccticut 06824

Phone: 203-255-3805 Fax: 203-380-1289

E-mail: Mac@LeaskBV.Com Web Page: www.LeaskBV.com

John M. Leask, II

(Mac)

CPA/ABV, CVA

Do I really need

an appraisal expert?

DIY valuations can lead to inequitable divorce settlements

![]() wners usually have a general sense of what their businesses are worth based on competitor sales or industry “rules of thumb.” But gut instinct or appraisal folklore may be off the mark — and these metrics rarely stand up in court.

wners usually have a general sense of what their businesses are worth based on competitor sales or industry “rules of thumb.” But gut instinct or appraisal folklore may be off the mark — and these metrics rarely stand up in court.

When divorcing spouses own a business, it’s usually their biggest, most illiquid asset. Why guess at its value — or leave it to the whim of the court? An appraiser can bring concrete market evidence and other resources to the table.

Proven valuation techniques

Appraisers typically use several generally accepted methods to value businesses, including the adjusted book value, guideline public company, merger and acquisition, capitalization of earnings and discounted cash flow methods. Courts prefer these proven techniques.

Shortcuts, such as industry rules of thumb, net book value or buy-sell formulas, rarely pass muster. In

addition, if a divorce case ends up in court, a valuator can serve as a compelling expert witness and provide an edge in any negotiations.

Insight into selling terms

Unlike real estate transactions, which are a matter of public record, private business sales aren’t publicly disclosed. But valuators have access to proprietary databases of private sales transactions reported by business brokers that can provide insight into current selling terms for an industry.

For example, buyers sometimes don’t pay 100% cash up front. Terms of a deal may involve stock transfers, noncompete agreements and postsale consulting agreements. In addition, installment sales and seller notes may be used to finance deals.

Before splitting up assets in a divorce, the parties should consider whether comparable transactions include noncash terms — such as stock or a noncompete agreement — or payments spread over a period of time. If buyouts are based on comparables having these features but no adjustment is made for them, the concluded value could be substantially incorrect.

To illustrate: Suppose three comparables sold for an average pricing multiple of one times revenues, but all the deals were paid 20% up front with the remainder spread over five years. It would be inequitable for the court to expect one spouse to buy out the other today at a multiple of one times revenues. A fairer approach would be to incorporate installment payments into the settlement — or to adjust the pricing multiple to reflect a cash-equivalent price.

When both spouses have operated a business before a divorce, a valuator might suggest incorporating an earnout (where a portion of the selling price is contingent on future performance) into the buyout agreement. Buyouts with earnout clauses ensure both

parties share in the risk of business failure after the loss of a key person (for example, the spouse who was bought out).

Menu of adjustments

A business’s book value and its fair market value are rarely synonymous, which is why professional valuators consider a series of possible adjustments when appraising a business for divorce. Thus, the balance sheet might not report all of the assets — for example, internally generated intangibles aren’t reported on a GAAP financial statement. Or there may be contingent liabilities, such as pending lawsuits or built-in capital gains tax liabilities.

If a divorce case ends up in court, a valuator can serve as a compelling expert witness and provide an edge in any negotiations.

On the income statement side, unscrupulous owners sometimes defer revenue recognition or overstate expenses to lower value, which may require an adjustment. Other common adjustments include

reasonable replacement compensation, quasibusiness expenses, and nonrecurring income and expenses. These adjustments must be identified and quantified before applying pricing multiples or discounting future earnings.

Case law repertoire

An experienced valuator also can advise attorneys in divorce cases about valuation-related cases in the particular jurisdiction. Relevant issues include the appropriate standard of value, the appraisal date and local courts’ treatment of buy-sell agreements and goodwill.

An understanding of legal precedent in other jurisdictions can be helpful, too. Family courts sometimes consider cases in other states — or even U.S. Tax Court cases — especially if the state hasn’t ruled on a similar case or if state case law is contradictory.

A smart investment

In today’s era of frugality, divorcing couples may wonder whether appraisal expertise is a must-have — or whether the parties can work out their settlement on their own. But appraisal and expert witness fees are usually money well spent when the marital estate includes a closely held business interest.

Valuators help the parties accurately value assets. Without reliable appraisal evidence, it’s unlikely that complex marital estates will be equitably distributed. l

Buy-sells may not reflect fair market value

If a business has a buy-sell agreement in place, it may be tempting to use its prescribed formula — or a previous transaction — rather than pay for an up-to-date, formal appraisal. But even the most comprehensive buy-sell may not hold up when challenged.

For example, in the recent case Wood v. Wood, the husband owned a 30% interest in a privately held flooring store. The Missouri Appellate Court struck down the wife’s value of approximately $1.063 million for the interest, a number based solely on a buy-sell formula. Instead, the court advised the trial court to reconsider the fair market value of $325,000 set forth by the husband’s expert.

His lower appraisal factored in goodwill, minority ownership and the recession. By comparison, the wife’s expert used a starting point of $3 million — the historical value of the entire business in 2007 when the shareholders bought the store — rather than the fair market value on the date of divorce.

Although buy-sell agreements and previous transactions are worth considering, today’s fair market value may deviate from these indicators. There’s no substitute for a current professional appraisal.

Valuators can play a supporting

role in business growth strategies

![]() mong the many roles valuators play in facilitating a company’s success, one of the most overlooked may be their support in evaluating strategic investmentdecisions. Valuators have many tools at their disposal that can help management determine the winning investment strategy.

mong the many roles valuators play in facilitating a company’s success, one of the most overlooked may be their support in evaluating strategic investmentdecisions. Valuators have many tools at their disposal that can help management determine the winning investment strategy.

Methods for acting

Businesses seeking growth have several

choices, including:

1. Organic or internal growth. Generally this is the slow and steady path. Strategies include building a new plant, purchasing new machinery, developing a new product or service and expanding into new markets.

Building from within isn’t without drawbacks, however. New products might cannibalize existing ones, or new target markets might reject product extensions. Opening another facility in a new location also involves ahost of uncertainties, including underutilized capacity, unexpected sources of competition and skilled labor shortages.

2. Mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Buying another company is the fast track for growth. M&As typically provide assets and an established track record, including immediate cash flow, an assembled workforce, a pre-existing client base and customer referrals.

They make the most sense when the value of the combined entity is greater than the sum of its parts, as in a strategic purchase. Strategic value represents

the value of a business to a particular investor based on that investor’s investment requirements and expectations. For such buyers, acquisitions typically

create value via economies of scale, operating syner- gies and cross-selling opportunities. Acquisitions don’t always pan out, however. Incongruent corporate

cultures, incompatible operating systems, unrealistic

value estimates and seller misrepresentations can

lead to failure.

3. Joint ventures. Joint ventures and other contrac- tual relationships, such as licensing and franchising, allow businesses to grow with minimal capital infusion. By starting slowly, two organizations can test their congruence and, if compatible, add incremental layers over time. Nevertheless, conducting financial due diligence is critical.

Using financial tools

Businesses facing growth opportunities may have limited resources to pursue all of their ideas. When prioritizing and selecting expansion alternatives, projected financial statements are useful.

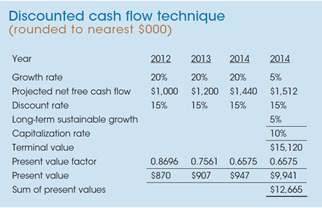

However, projections ignore the time value of money because, by definition, they describe what’s going to happen given a set of circumstances. So it’s difficult to compare detailed projections against other investments a business might be considering. Valuators, therefore, use other financial tools — such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR) and accounting payback period calculations — to generate comparative metrics.

Valuators may use the accounting payback period tool to estimate how long an investment will take to recoup its initial cost.

In an NPV analysis, a valuator projects each alternative’s expected cash flows. Then he or she discounts each period’s projected cash flow to its present value, using a discount rate proportionate to its risk. If the sum of these present values — the NPV — is

greater than zero, the investment is worthwhile. When comparing alternatives, higher NPV is generally better.

IRR relies on the same data as NPV. But it computes the required return that results in a zero NPV. A valuator compares a company’s IRR to pre-established hurdle rates (often the cost of capital). For example, if a new product line is projected to generate an IRR of 20% and the hurdle rate is 15%, the new product makes sense. When comparing competing alternatives, the one with the highest IRR is typically preferred.

Finally, valuators may use the accounting payback period tool to estimate how long an investment will take to recoup its initial cost. Using this tool, the payback for a machine that costs $200,000 and generates $40,000 in annual incremental profits would be five years.

Understand the valuator’s role

Clearly, poor investment decisions can lead to bankruptcy.So business owners can benefit from understanding the supporting role valuators can play in helping their companies pursue the growth strategies most likely to succeed.

Replacement compensation Q&A

Why these valuations pose challenges for experts

![]() wner replacement compensation refers to the amount an unrelated person would be paid for performing the same duties that an owner performs at the subject company. It includes salaries and commissions, payroll taxes, benefits and perks. Estimating replacement compensation is especially challenging when owners receive noncash perks, such as stock or stock options. Here is a brief look at some common questions related to replacement compensation.

wner replacement compensation refers to the amount an unrelated person would be paid for performing the same duties that an owner performs at the subject company. It includes salaries and commissions, payroll taxes, benefits and perks. Estimating replacement compensation is especially challenging when owners receive noncash perks, such as stock or stock options. Here is a brief look at some common questions related to replacement compensation.

Q: How does owners’

compensation affect value?

A: The more owners pay themselves, the lower the

company’s reported earnings will be. Value typically

is based on earnings or some income stream that is

affected by owners’ compensation. Unless adjustments

are made, above-market owners’ compensation

lowers a company’s value (and vice versa).

Regardless of whether valid reasons exist for above- or below-market compensation, appraisers customarily adjust for reasonable replacement compensation to accurately value a controlling interest. However, valuators generally don’t adjust for replacement compensation when valuing a minority interest. That’s because minority shareholders lack the requisite control to alter owners’ compensation.

Q: Why might actual and replacement compensation differ?

A: Actual compensation often differs from replacement compensation. Differences may be justified — for example, if the owners personally guarantee the company’s debt or possess advanced skills and training that warrant higher salaries.

Sometimes owners have tax incentives to tinker with their compensation. A C corporation might pay abovemarket compensation in lieu of paying dividends, because the earnings of a C corporation (from which dividends are paid) are taxed at the corporate level and then dividends are taxed again at the personal level. Conversely, an S corporation or partnership — which isn’t taxed at the corporate level — might undercompensate its owners and instead make larger distributions to them, which minimizes payroll taxes.

The IRS and local taxing authorities are on the watch for these tax avoidance techniques. A valuator is sometimes called in to defend owners’ compensation levels for tax purposes.

Q: When is replacement compensation an issue?

A: Replacement compensation is a major contention point when a marital estate includes a private business interest. The owner-spouse’s compensation factors into the value of the business, as well as into alimony and child support payments.

Minority shareholders also may dispute replacement compensation. For example, the adjustment for reasonable replacement compensation was a major issue

in a recent minority shareholder dissension case, Hubbard v. Phil’s BBQ of Point Loma, Inc.

Here, the California Southern District Court upheld the trial court’s combined replacement compensation estimate of $610,000 for the CEO, COO and a market consultant, based on Economic Research Institute (ERI) executive compensation surveys. To arrive at this estimate, three court-appointed appraisers — one nominated by each side and the third nominated by the first two appraisers — submitted a single appraisal report.

On appeal, the plaintiff hired a fourth expert who unsuccessfully claimed that executive replacement compensation for these executive functions should be only $195,000, based on Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data for California. Overall, the court accepted the three experts’ joint appraisal — including the adjustment for replacement compensation.

Q: What sources support replacement compensation estimates?

A: Besides ERI and BLS publications, other common sources of compensation data include, but are not limited to:

- Salary Guide (Robert Half International),

- Annual Statement Studies (The Risk Management Association),

- Statistics of Income: Corporation Income Tax Returns (a federal government publication),

- Executive Compensation survey (Compdata Surveys),and

- Relevant trade association publications and information from executive recruiters.

Valuators need accurate job descriptions before researching these sources and also can consider personal factors such as the owners’ qualifications, age, health and hours worked. External factors — such

as company size and financial condition, geographic location, industry trends, and economic conditions — also come into play.

Q: Who can objectively estimate replacement compensation?

A: Owners’ compensation is one of the biggest, most subjective expenses on the books because what’s “reasonable” often is in the eye of the beholder. But experienced valuators know how to support their replacement compensation calculations with thorough, well-founded research that’s likely to withstand IRS and court scrutiny.

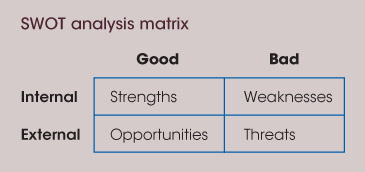

Visual aids have a strong impact

Concise visual aids — combined with succinct expert testimony — can help laypeople understand complex financial matters. Take, for example, a valuator who uses the guideline private transaction method to value a business for divorce purposes. He employs regression analysis to derive a pricing multiple from more than 40 comparables.

Because statistical nuances — such as the line of best fit and R-squared, a measure of reliability — are beyond most people’s expertise, the expert prepares a scatter-graph that compares sales price to operating cash flow. His demonstrative exhibit first plots the individual transactions as dots on the graph. Then the computer model adds the line of best fit.

This visual aid helps the judge better understand the expert’s analysis. Quite simply, it’s memorable and the judge may even mention it in the court opinion.

Valuation experts can use several types of visual aids. For instance, a line graph might demonstrate sales and expense trends over the previous five years to support a lost profits claim. Or a flowchart might be used to depict a shareholder’s percentage ownership in a multitiered business organization, such as a partnership that owns stock in an LLC having fractional interests in several real estate ventures. Not only can visual aids facilitate expert testimony, but they also can be attached as appendices to help explain a lengthy written appraisal report.

Thoughtful, relevant visual aids make a valuation expert stand out and appear better prepared for trial. The next time your eyes start to glaze over when a valuator explains complex financial issues, consider requesting visual aids to help him or her more effectively communicate value conclusions.

This publication is distributed with the understanding that the author, publisher and distributor are not rendering legal, accounting or other

professional advice or opinions on specific facts or matters, and, accordingly, assume no liability whatsoever in connection with its use. In

addition, any discounts are used for illustrative purposes and do not purport to be specific recommendations. ©2012 VVjf13

765 Post Road, Fairfield, Connecticut 06824

PRSRT STANDARD

US POSTAGE

PAID

PERMIT NO. 57

FAIRFIELD, CT

John M. Leask II (Mac), CPA/ABV, CVA, values 25 to 50 businesses annually. Often, Mac’s valuations,oral or written, are compiled in conjunction with the purchase or sale of a business, to assist shareholders prepare buy/sell agreements, or to set values when shareholders purchase the interest of a retiring shareholder.Here are examples

- Due Diligence & Assist with Purchase of a Business. Mac has assisted purchasers of businesses by determining or reviewing the offer. He helps negotiate the price, perform due diligence prior to closing and/or helps structure and secure financing. Services have included, but are not limited to, verifying liabilities and assets, reviewing sales and expense records, and identifying critical issues relating to future success, and helping management plan future operations.

- Family Limited Liability Partnerships, Companies & Closely Held Businesses. Mac regularly values various sized business interests for estate and gift tax purposes. He provides assistance to estate and trust experts during audits of reports prepared by other valuators.

Mac also helps business owners and their CPAs and/or lawyers in the following ways:

- Planning — prior to buying or selling the business

- Prepare valuation reports in conjunction with filing estate and gift tax returns

- Plan buy/sell agreements and suggest financing arrangements

- Expert witness in divorce & shareholder disputes

- Support charitable contributions

- Document value prior to sale of charitable entities

- Assist during IRS audits involving other valuators’ reports

- Succession planning

- Prepare valuation reports in conjunction with pre-nuptial agreements

- Understanding firm operations & improving firm profitability

More information about the firm’s valuation services (including case studies) may be found at www.LeaskBV.com.

To schedule an individual consultation or to discuss any other points of interest, Mac may be reached at 203 – 255 – 3805.

The fax is 203 – 380 – 1289, and e-mail is Mac@LeaskBV.Com.

If you have a business valuation problem, Mac is always available to discuss your options — at no charge.

ost appraisals call for going-concern value — that is, the value of a business as if it will continue to operate profitably into perpetuity. Going-concern value is a function of future cash flows.

ost appraisals call for going-concern value — that is, the value of a business as if it will continue to operate profitably into perpetuity. Going-concern value is a function of future cash flows.

unless the company’s assets are highly specialized or there is a limited pool of interested buyers who are ready to act quickly.

unless the company’s assets are highly specialized or there is a limited pool of interested buyers who are ready to act quickly.

ourts often struggle with how to interpret statutory fair value in shareholder disputes, including whether to discount business interests for built-in capital gains tax. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi recently granted a dollar-for-dollar reduction for this tax liability. The oppressed shareholder case demonstrates how courts may be persuaded by thorough, credible expert appraisal evidence.

ourts often struggle with how to interpret statutory fair value in shareholder disputes, including whether to discount business interests for built-in capital gains tax. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Mississippi recently granted a dollar-for-dollar reduction for this tax liability. The oppressed shareholder case demonstrates how courts may be persuaded by thorough, credible expert appraisal evidence.

ehen valuing a business interest for tax purposes, the taxpayer might wonder, “Why isn’t my discount for lack of marketability (DLOM) 50% or more?” Conversely, the IRS might contend that no DLOM applies whatsoever. A battle usually ensues.

ehen valuing a business interest for tax purposes, the taxpayer might wonder, “Why isn’t my discount for lack of marketability (DLOM) 50% or more?” Conversely, the IRS might contend that no DLOM applies whatsoever. A battle usually ensues.

Flotation costs (the costs of going public),

Flotation costs (the costs of going public),

n an ever more virtual world, business owners increasingly depend on intellectual property (IP) to generate value for their companies. But determining the value of IP — be it patents, copyrights or trademarks — can be challenging. In addition to obtaining guidance from professional appraisal organizations, appraisers use several methods to determine what these intangible assets are really worth.

n an ever more virtual world, business owners increasingly depend on intellectual property (IP) to generate value for their companies. But determining the value of IP — be it patents, copyrights or trademarks — can be challenging. In addition to obtaining guidance from professional appraisal organizations, appraisers use several methods to determine what these intangible assets are really worth.

The economic benefits, direct or indirect, that the asset is expected to provide to its owner during its life,

The economic benefits, direct or indirect, that the asset is expected to provide to its owner during its life,

ome clients mistakenly use the terms “discount rate” and “capitalization rate” (cap rate) interchangeably. But they are two different concepts. It’s important to understand how these terms differ to

ome clients mistakenly use the terms “discount rate” and “capitalization rate” (cap rate) interchangeably. But they are two different concepts. It’s important to understand how these terms differ to

t would be wonderful if the future just took care of itself. But in the case of buy-sell agreements, the future depends on what’s done today. For businesses, an unforeseen event such as the death of an owner can quickly turn into a crisis that could lead to a transfer of ownership.

t would be wonderful if the future just took care of itself. But in the case of buy-sell agreements, the future depends on what’s done today. For businesses, an unforeseen event such as the death of an owner can quickly turn into a crisis that could lead to a transfer of ownership.

efore you pick up the phone to hire a valuation professional, you need to think about what you’re looking to achieve and what you should expect throughout the appraisal process. Business owners, attorneys and other interested parties who understand valuation terms, anticipate information requests and provide reasonable timelines will help minimize errors, surprises and haste.

efore you pick up the phone to hire a valuation professional, you need to think about what you’re looking to achieve and what you should expect throughout the appraisal process. Business owners, attorneys and other interested parties who understand valuation terms, anticipate information requests and provide reasonable timelines will help minimize errors, surprises and haste.

Budgets, business plans and forecasts,

Budgets, business plans and forecasts,

fundamental question concerning any business transaction is whether it’s a fair deal. But how is fairness determined? A fairness opinion stating whether a proposed merger, acquisition or other transaction seems fair in light of the financial circumstances is typically the first step, and it can give you peace of mind if you’re inexperienced or unsure

fundamental question concerning any business transaction is whether it’s a fair deal. But how is fairness determined? A fairness opinion stating whether a proposed merger, acquisition or other transaction seems fair in light of the financial circumstances is typically the first step, and it can give you peace of mind if you’re inexperienced or unsure

hen choosing a business appraiser, you want the best. But it’s important to remember that not all experts are created equal. How do you know whether the appraiser you’re about to hire has what it takes — or whether an opposing expert has the required expertise?

hen choosing a business appraiser, you want the best. But it’s important to remember that not all experts are created equal. How do you know whether the appraiser you’re about to hire has what it takes — or whether an opposing expert has the required expertise?

iscounts for lack of control and marketability are common in business valuation. But a lesser-known discount for blockage may apply when valuing large blocks of public stock with limited trading volume.

iscounts for lack of control and marketability are common in business valuation. But a lesser-known discount for blockage may apply when valuing large blocks of public stock with limited trading volume.

perating a business without a valid buysell agreement is like driving a car without insurance. Buy-sell agreements provide much-needed protection when an owner involuntarily leaves — or voluntarily wants out of the business. A comprehensive agreement not only defines the term “value,” but it also incorporates buyout terms and includes provisions for various buy/sell scenarios and contingencies.

perating a business without a valid buysell agreement is like driving a car without insurance. Buy-sell agreements provide much-needed protection when an owner involuntarily leaves — or voluntarily wants out of the business. A comprehensive agreement not only defines the term “value,” but it also incorporates buyout terms and includes provisions for various buy/sell scenarios and contingencies.

Effective date (termination date or date of legal filing),

Effective date (termination date or date of legal filing),

uying or merging with another company to increase market share, compensate for operational weaknesses or acquire talented workers in scarce labor markets may seem like a no-brainer. But despite how great the deal looks on paper, many mergers and acquisitions (M&As) fall through because they simply don’t make sound financial sense. A valuator can help businesses avoid making a major M&A mistake.

uying or merging with another company to increase market share, compensate for operational weaknesses or acquire talented workers in scarce labor markets may seem like a no-brainer. But despite how great the deal looks on paper, many mergers and acquisitions (M&As) fall through because they simply don’t make sound financial sense. A valuator can help businesses avoid making a major M&A mistake.

and investors will require a higher return, thereby increasing the company’s cost of capital.

and investors will require a higher return, thereby increasing the company’s cost of capital.

he IRS developed the excess earnings (or formula) method in the 1920s as a way to compensate breweries and distilleries for intangible value lost during the Prohibition era. Surprisingly, appraisers still use this method to value businesses in a variety of industries.

he IRS developed the excess earnings (or formula) method in the 1920s as a way to compensate breweries and distilleries for intangible value lost during the Prohibition era. Surprisingly, appraisers still use this method to value businesses in a variety of industries.

hen planning to merge with or acquire another company, a business owner needs to identify what’s actually being sold and estimate what those assets are really worth. Often the most valuable assets — such as goodwill, brand names, customer lists and patents — don’t appear on the balance sheet.

hen planning to merge with or acquire another company, a business owner needs to identify what’s actually being sold and estimate what those assets are really worth. Often the most valuable assets — such as goodwill, brand names, customer lists and patents — don’t appear on the balance sheet.

rational investor would never buy an asset without a reasonable expected return. An investment’s value is based on what economic benefits — whether in the form of dividends, interest or cash flow — it’s expected to generate in the future. Projected cash flow is thus an important measure of future economic benefits.

rational investor would never buy an asset without a reasonable expected return. An investment’s value is based on what economic benefits — whether in the form of dividends, interest or cash flow — it’s expected to generate in the future. Projected cash flow is thus an important measure of future economic benefits.